Neutron stars, the remnants of massive stars, are among the densest objects in the universe. When stars with masses between eight and twenty times that of the Sun exhaust their nuclear fuel, they can no longer support themselves against gravitational collapse. This results in a dramatic supernova explosion, leaving behind a compact stellar remnant roughly the size of a city. Despite their small scale, neutron stars can contain more mass than the Sun, creating conditions that challenge the limits of our understanding of physics.

These collapsed stars reach densities around 1017 kilograms per cubic meter. This is comparable to compressing the mass of Mount Everest into a teaspoon. At such extreme densities, atomic structures disintegrate, forcing protons and electrons to merge into neutrons. This transformation generates neutron degeneracy pressure, a quantum force that halts further collapse and stops the formation of black holes. The result is an object with immense gravitational pull, powerful magnetic fields, and rapid rotation, presenting astronomers with a unique laboratory for studying fundamental physics.

Formation and Structure of Neutron Stars

Neutron stars form through core-collapse supernovae. When fusion within a massive star’s iron core ceases to generate energy, the internal pressure diminishes. Electrons are forced into protons, resulting in the creation of neutrons, alongside a torrent of neutrinos that carry away most of the star’s gravitational binding energy. The subsequent collapse of the core rebounds violently, ejecting the outer layers while compressing the core into a neutron star.

Structurally, these stellar remnants possess distinct internal layers shaped by extreme pressure. A thin outer crust consists of tightly packed atomic nuclei, while deeper layers experience a phenomenon known as “neutron drip,” where neutrons escape from atomic bonds. Beneath this crust lies a superfluid outer core dominated by free neutrons and exotic particles, potentially transitioning into quark matter in the innermost regions.

The stability of neutron stars is limited by the Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff mass boundary, estimated to be around 2.2 solar masses. If a neutron star exceeds this threshold, neutron degeneracy pressure can no longer support it, leading to further collapse into a black hole—a clear demarcation between stellar remnants and spacetime singularities.

Rotation and Magnetic Fields

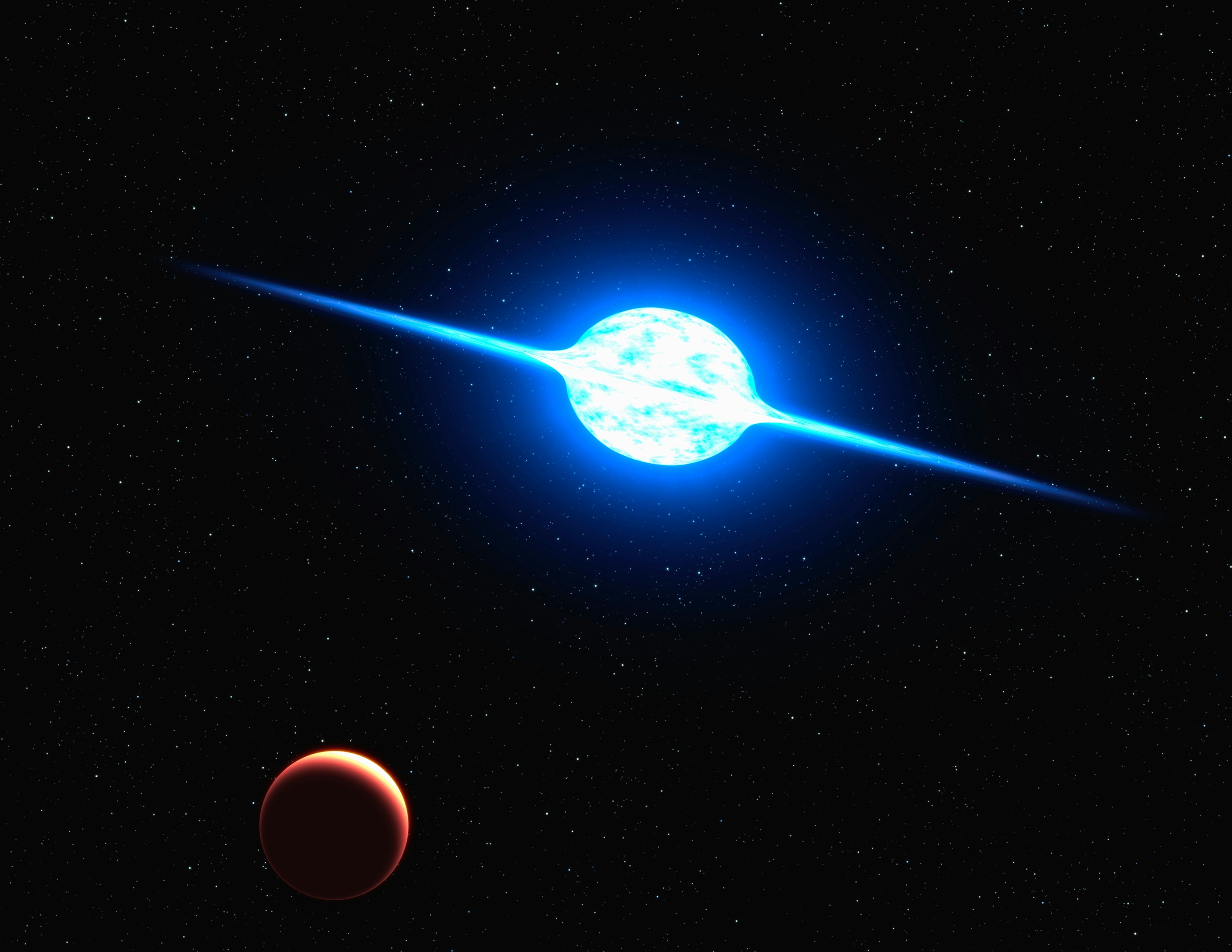

Neutron stars conserve angular momentum as they collapse, leading to extraordinarily high rotation speeds. For instance, a progenitor star that originally spins once per day may evolve into a neutron star rotating hundreds of times per second. Some millisecond pulsars reach rotational frequencies exceeding 700 hertz, emitting precisely timed radio pulses detectable across vast distances in the Milky Way.

Among neutron stars, magnetars are a rare subclass characterized by their intense magnetic fields, which can exceed 1015 gauss. These fields are trillions of times stronger than Earth’s magnetic field. The immense stress on the star’s crust can cause it to fracture during starquakes, resulting in bursts of gamma rays that surpass typical supernova outputs. Such phenomena illustrate how neutron stars can store and release colossal amounts of energy through magnetic processes alone.

Timing irregularities, known as glitches, provide further insights into the exotic interiors of these stellar remnants. These sudden shifts in spin rate are believed to occur when superfluid vortices within the core unpin, redistributing angular momentum and momentarily altering the star’s rotation with remarkable precision.

Gravitational-wave astronomy has revolutionized our understanding of neutron stars. The detection of GW170817 confirmed that merging neutron stars emit ripples in spacetime, measurable across hundreds of millions of light years. These merger events have established a direct link between neutron stars and the formation of heavy elements such as gold and platinum, highlighting their significance in shaping cosmic structure.

Observations have enabled scientists to refine the neutron star equation of state, narrowing possible models of their radius and density. Typical neutron stars measure approximately 11 to 13 kilometers in diameter, ruling out both overly soft and extremely rigid internal matter models. Recent observations from the NICER mission aboard the International Space Station have further honed these measurements. By tracking X-ray hotspots on rotating neutron stars, astronomers can confirm mass-radius relationships that support dense yet stable cores.

Neutron stars also play a crucial role in galactic chemistry. Binary neutron star mergers expel neutron-rich material that enriches galaxies with heavy elements essential for planets and life. Without these stellar remnants, many elements beyond iron would be exceedingly rare, underscoring their importance in the universe.

As observational tools continue to advance, our understanding of neutron stars is poised to deepen. Gravitational waves, X-ray mapping, and precise timing arrays are unveiling the processes by which neutron stars form, evolve, and collide across cosmic time. Each new discovery brings researchers closer to comprehending matter under conditions that define some of the universe’s most extreme environments.

Neutron stars, with their extreme gravity, density, magnetism, and rotation, challenge our understanding of nuclear physics, relativity, and quantum mechanics. As scientists continue to investigate these stellar remnants, they offer a glimpse into the fundamental laws of nature and the complex universe in which we reside.