Research has unveiled significant insights into the organized craft production of ancient communities in the Sierras de Córdoba, Argentina, focusing on the manufacturing techniques of bone arrow points. A study led by Dr. Matías Medina and his colleagues, Sebastián Pastor and Gisela Sario, highlights how these communities operated during the Late Prehispanic Period, which spans from approximately 1220 to 330 cal BP.

For many years, understanding the diverse bone materials utilized by these prehistoric societies remained limited. The new findings, published in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, fill a crucial gap, revealing how these communities not only crafted tools but also structured their daily lives around their craft production.

Exploring Prehistoric Economies

The Late Prehistoric Period in the Sierras de Córdoba was characterized by a mixed economy that integrated hunting, gathering, and agriculture. This approach allowed communities to maintain mobility, occupying seasonal camps and adapting their lifestyles to the most effective subsistence strategies available. Despite the significance of bone tools in their material culture, these artifacts have often been overlooked in archaeological studies.

Dr. Medina noted the historical scarcity of publications focused on bone technology in South America. He emphasized that previous archaeological work primarily aimed to establish chronological frameworks rather than to analyze the specific manufacturing techniques of artifacts. The study of the bone arrow points from the Sierras de Córdoba marks a pivotal shift in this narrative.

Manufacturing Techniques and Insights

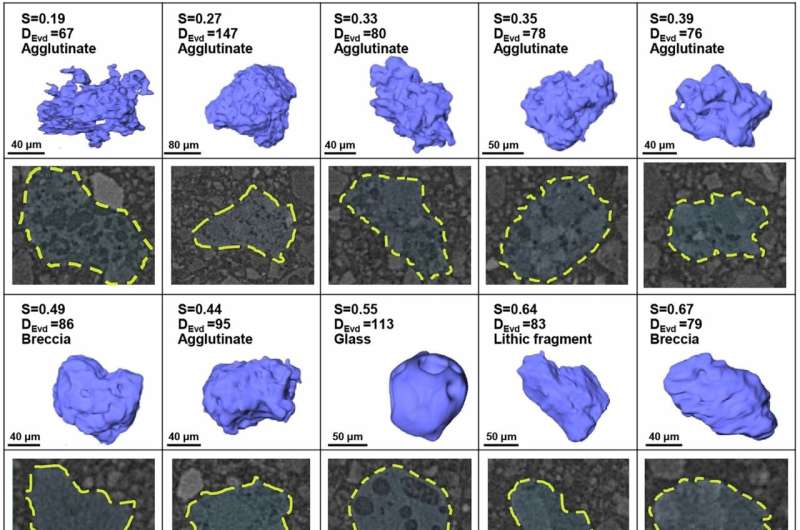

To gain a deeper understanding of these ancient practices, the research team examined 117 bone artifacts housed in the Museo Arqueológico Numba Charava. These artifacts were collected non-systematically throughout the 20th century from various sites in the southern Punilla Valley, which resulted in many lacking precise provenance.

The analysis found that the primary raw material for the arrow points was derived from the bones of the guanaco, a species hunted for food. Bones from other animals, such as pampas deer, were less common. The crafting process began with splitting the long bones, known as metapodia, lengthwise to create workable blanks. These blanks were then flattened, scraped, and shaped into arrowheads. Some points featured decorative elements, including incised designs, which Dr. Medina noted were rare, with only three such examples documented in archaeological literature.

The study proposes that these decorative arrow points served a dual purpose: while primarily used for warfare, they also expressed social identity and cultural affiliation. This is particularly significant, as it suggests that the arrow points were not just functional objects but also carried deeper cultural meanings.

This research not only sheds light on the specific techniques used in the Southern Punilla Valley but also has broader implications for understanding similar technological practices in other regions. Dr. Medina pointed out the necessity for comparative studies with neighboring areas, such as the Low Paraná and Uruguay River floodplains, to explore variations in bone technology based on local resources.

The discoveries made through this research contribute significantly to the understanding of how ancient communities organized their tool-making processes. The findings suggest that the production of arrow points was a time-consuming but standardized practice, likely passed down through generations within nuclear families. This reinforces the notion that the nuclear family served as the primary social unit for both food and tool production during this period.

As the study continues to generate interest, it highlights the importance of revisiting archaeological materials to uncover the complexities of prehistoric life. The research stands as a testament to the potential for further discoveries that can reshape our understanding of ancient societies and their craftsmanship.

This article has been fact-checked and reviewed to ensure accuracy and credibility. For ongoing updates in science and archaeology, readers are encouraged to explore resources that support independent journalism.