Recent discoveries in the field of astronomy have highlighted the existence of Earth-like exoplanets, yet researchers have yet to find an exact twin of our planet. Among the notable candidates is Kepler 452b, which orbits a G-type star similar to the sun. Despite its promising location in the habitable zone, this planet is approximately 1.6 times the size of Earth, prompting questions about its suitability for life.

Over the past 30 years, astronomers have identified more than 6,000 planets beyond our solar system, according to data from NASA. As the hunt for potentially habitable worlds continues, the central inquiry remains: Could any of these planets support extraterrestrial life? Stephen Kane, a planetary astrophysicist at the University of California, Riverside, cautions against overhyping the search for “Earth-like” planets. He notes that “to be honest, we really haven’t found anything like that at all” when it comes to planets matching Earth’s size and orbiting a sun-like star.

The challenge lies in the limited information available about these distant worlds. Most knowledge is based on indirect measurements of size, mass, and orbit, with detailed atmospheric data largely absent. According to NASA, while astronomers have successfully imaged a few dozen gas giants, Earth-sized planets are too small and dim for direct observation. Kane explains, “We don’t know what they look like, even on a single pixel. Everything we do know, we infer from indirect observations.”

Many of the rocky exoplanets discovered thus far orbit M dwarf stars, commonly known as red dwarfs. These stars possess narrower habitable zones and emit higher levels of radiation compared to G-type stars. This raises concerns about the potential for life on planets in these systems. For example, the TRAPPIST-1 system, located about 39 light-years away in the constellation Aquarius, features seven rocky planets within its habitable zone. However, observations from the James Webb Space Telescope suggest that some of these planets may lack atmospheres due to the volatile nature of their red dwarf star.

Similarly, three exoplanets orbiting Teegarden’s Star, located 12 light-years away in the constellation Aries, exhibit the right size and distance from their star for potential habitability. Yet, being part of a red dwarf system raises significant concerns about their capacity to support life, as noted by the Infrared Processing and Analysis Center at Caltech.

The challenge of finding truly Earth-like planets is compounded by the nature of exoplanet detection methods. Most are discovered through the transit method, which requires precise alignment between the planet, its star, and Earth to measure changes in light. The Kepler Space Telescope, which operated from 2009 to 2018, observed around 170,000 stars, identifying approximately 2,700 exoplanets. This statistic implies that many potentially habitable exoplanets may not transit in a way that allows for observation.

Kane suggests a shift in the approach to exoplanet discovery. Other techniques, such as measuring a star’s “radial velocity” or wobble, can provide vital information about the number, mass, and distance of orbiting planets.

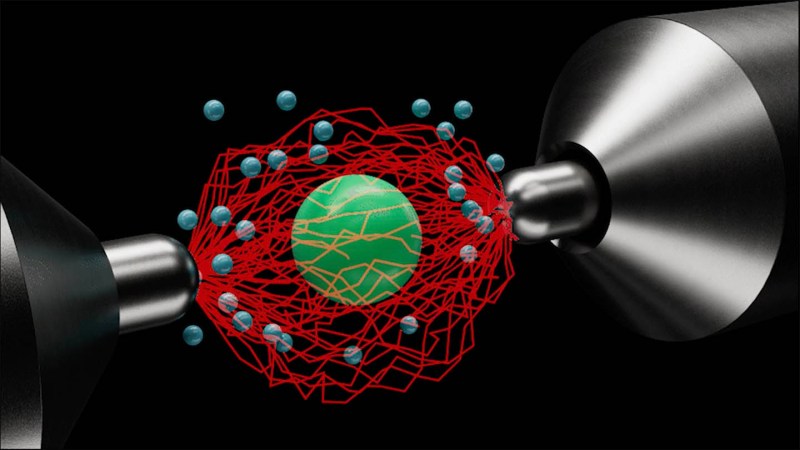

Looking to the future, the direct imaging of rocky exoplanets could soon become a reality. NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, scheduled for launch in 2027, aims to overcome current limitations by employing a coronagraph to block light from stars, allowing fainter exoplanets to come into view. Additionally, the proposed Habitable Worlds Observatory (HabWorlds), tentatively set for the late 2030s or early 2040s, would be the first telescope designed specifically to identify alien biosignatures. It is expected to have the capability to detect atmospheric molecules indicative of life.

As astronomers continue to explore the cosmos, it is likely that new targets will emerge, alongside the advancements in technology. Kane emphasizes the importance of patience, stating, “The last 20 years have been incredible. Let’s see where we are in another 20 years.” The quest for a true counterpart to Earth remains ongoing, with each discovery offering insights into the potential for life beyond our planet.