Recent research published in *The Planetary Science Journal* reveals significant findings regarding potential cryovolcanic activity on Pluto. A team of scientists investigated the Kildaze caldera, located in the dwarf planet’s Hayabusa Terra region, to better understand its geological processes. This study sheds light on how Pluto, despite its great distance from the Sun, may still exhibit signs of geological activity.

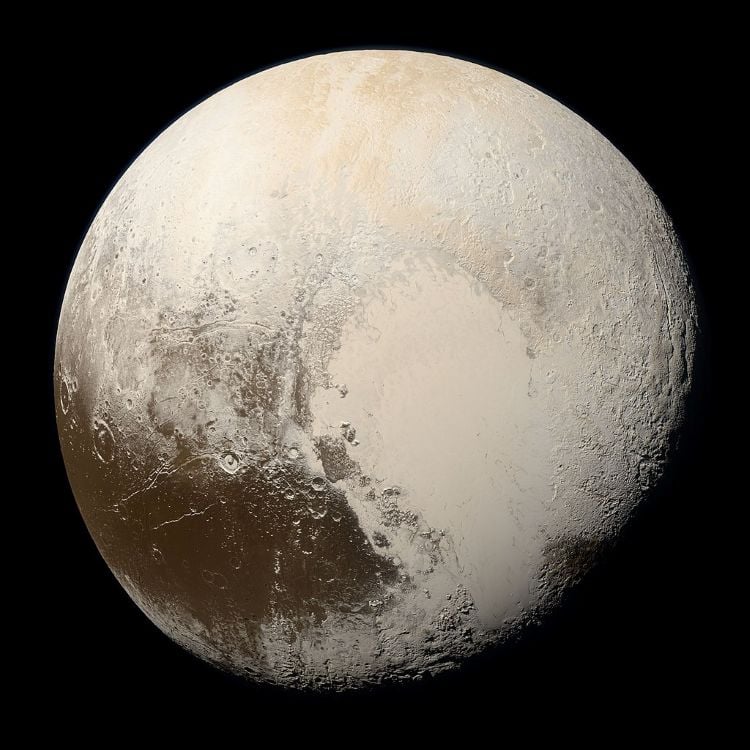

The researchers utilized images captured by NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft during its historic flyby of Pluto in July 2015. By comparing these images to known cryovolcanic sites on Pluto, including Virgil Fossae and Viking Terra, as well as analog sites on Earth and Mars, the team aimed to identify evidence of past cryovolcanism. Key analog sites on Earth included the Yellowstone caldera, Valles Caldera, and Long Valley Caldera, while Martian analogs featured collapsed pit craters in Noctis Labyrinthus, located within the Valles Marineris canyon system.

To analyze the characteristics of the Kildaze caldera, the researchers employed digital elevation models, elevation profiles, and 3D visualizations. Their findings indicate that the water ice present in Kildaze is estimated to be a few million years old, although it is significantly younger than Pluto itself. The study concludes that the caldera exhibits the size, structure, and composition indicative of a cryovolcano that may have experienced one or more eruptions, releasing approximately 1,000 km3 of cryolava.

Cryovolcanism, characterized by the eruption of icy materials instead of molten rock, has been observed on various celestial bodies throughout the solar system. Since the term was first introduced in 1987, scientists have documented cryovolcanic activity on worlds such as Ceres, Europa, Ganymede, Enceladus, and Titan. Possible sources of cryovolcanic activity include external factors like crater impacts and tidal heating, as well as internal heat generated from radioactive decay.

What makes the findings about Pluto particularly noteworthy is its position as the most distant known planet from the Sun. This distance raises questions about the sources of its geological activity, especially given that the Sun’s influence is likely minimal in this case. Researchers continue to explore whether Pluto’s internal heat results from tidal interactions with its largest moon, Charon, or from the decay of radioactive isotopes within its interior. A 2022 study published in *Icarus* suggested that the heat may stem from tidal interactions with Charon, which could have allowed Pluto to retain internal heat long after its formation.

While New Horizons remains the only spacecraft to have visited Pluto, several proposed missions aim to return to the dwarf planet. One concept involves an orbiter-lander combination powered by a fusion reactor, which could reach Pluto in approximately four years—a stark contrast to the nine years it took New Horizons to arrive.

As researchers continue to analyze the data provided by New Horizons, they hope to unlock more secrets of Pluto’s geological activity. The study of cryovolcanism offers a unique perspective on the processes that shape not only Pluto but also other icy worlds in our solar system. As inquiry into this intriguing subject progresses, the scientific community remains eager to discover what new insights will emerge in the coming years.