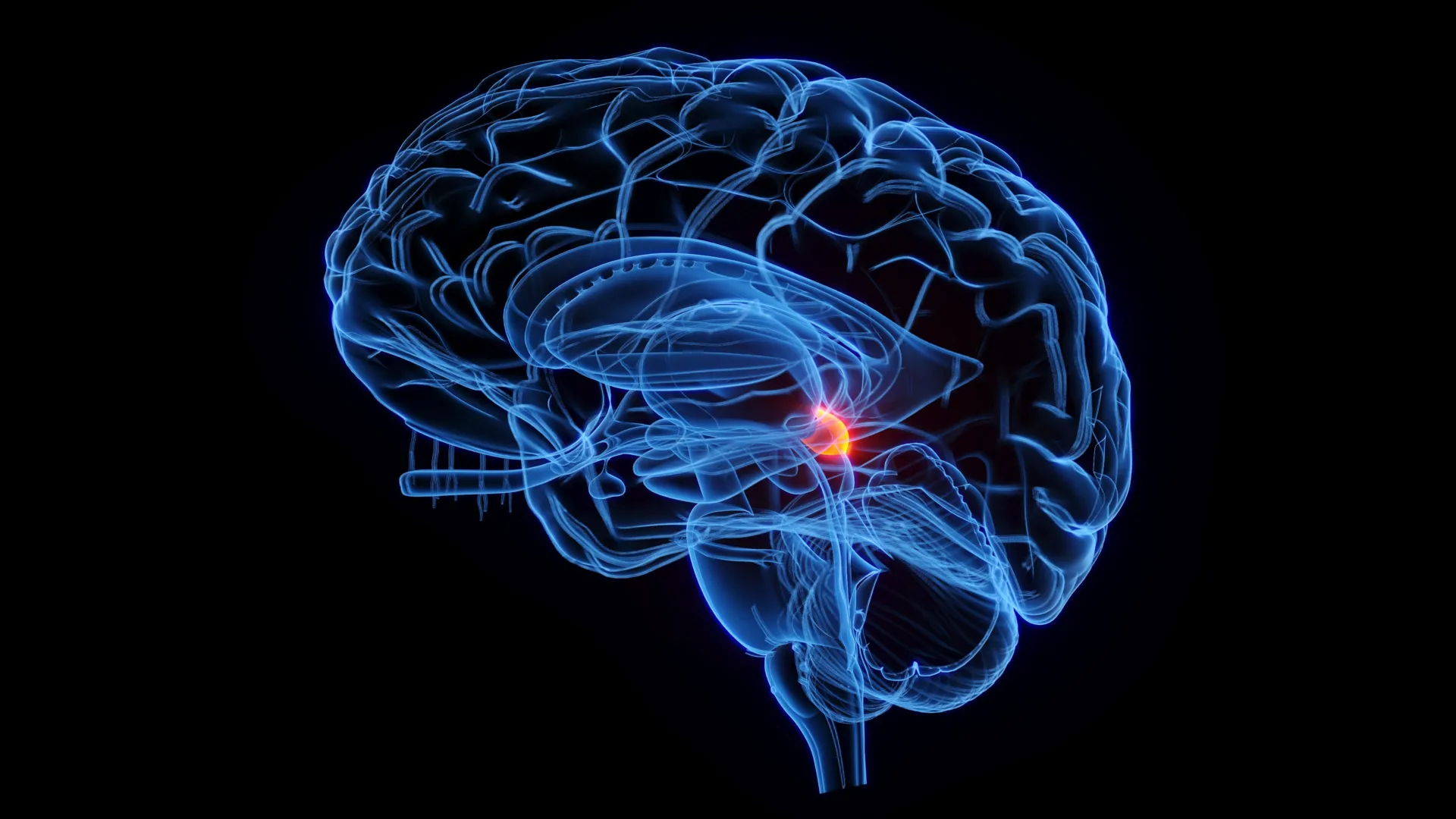

A recent study reveals that the superior colliculus, a primitive brain region over 500 million years old, plays a crucial role in visual processing, challenging long-standing beliefs that only the cortex is responsible for interpreting complex visual information. Research published in PLOS Biology indicates that this ancient neural structure can independently manage essential visual tasks, thereby reshaping our understanding of how the brain processes visual stimuli.

Revolutionizing Visual Processing Understanding

Traditionally, scientists believed that the cortex, the brain’s outer layer, was the exclusive site for complex visual computations. However, this new research highlights that the superior colliculus possesses neural networks capable of executing fundamental visual tasks. These circuits allow the brain to distinguish objects from their backgrounds and prioritize relevant visual cues.

Andreas Kardamakis, head of the Neural Circuits in Vision for Action Laboratory at the Institute for Neurosciences (IN), part of the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) and Universidad Miguel Hernández (UMH) of Elche, emphasizes, “For decades it was thought that these computations were exclusive to the visual cortex, but we have shown that the superior colliculus, a much older structure in evolutionary terms, can also perform them autonomously.” This suggests that the ability to analyze visual input and direct attention is not a recent development but rather an ancient mechanism embedded in our brain architecture.

Visual Radar and Its Cognitive Impact

The superior colliculus functions like a built-in radar, processing direct signals from the retina before they reach the cortex. This structure rapidly identifies important aspects of a visual scene, reacting to movements or sudden changes by guiding eye movements toward new stimuli. The research team employed advanced techniques, including patterned optogenetics and electrophysiology, to explore this process in detail.

By activating specific retinal pathways and recording responses in mouse brain slices, researchers discovered that the superior colliculus can suppress a primary visual signal when surrounding areas become more active. This is a key feature of center-surround processing, which enhances the detection of edges and contrasts in visual environments. Kuisong Song, co-first author of the study, notes, “This demonstrates that the ability to select or prioritize visual information is embedded in the oldest subcortical circuits of the brain.”

The findings indicate that mechanisms governing attention are deeply rooted in ancient brain structures, predating the evolution of higher cortical areas. This evolutionary perspective suggests that essential visual processing tasks, crucial for survival, have long relied on these fundamental circuits.

Understanding how these ancestral structures contribute to visual attention could provide insights into various disorders, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and sensory hypersensitivity. Kardamakis highlights that “disorders…may partly originate from imbalances between cortical communication and these fundamental circuits.”

The research team is now extending their studies to live animal models to investigate how the superior colliculus influences attention and manages distractions during goal-directed behaviors. This exploration aims to uncover the neurological basis of attention in a modern context where visual overload is increasingly common.

This significant research effort involved collaboration between esteemed institutions, including the Karolinska Institutet, KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Sweden, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the USA. Teresa Femenía, a researcher at IN CSIC-UMH, played a vital role in developing the experimental work.

Building on these findings, Kardamakis and colleague Giovanni Usseglio contributed to the Evolution of Nervous Systems series (Elsevier, 2025), which examines subcortical visual systems across different species. Their work reveals that structures analogous to the superior colliculus, found in various vertebrates, serve a common function of integrating sensory and motor information to direct gaze and attention. Kardamakis concludes, “Evolution did not replace these ancient systems; it built upon them. We still rely on the same basic hardware to decide where to look and what to ignore.”

This research received support from Spain’s State Research Agency, the Severo Ochoa Programme for Centres of Excellence, and other international funding bodies, reflecting its significance in the field of neurosciences.