Research from the University of Auckland has unveiled insights into the evolutionary origins of one of nature’s earliest motors, developed between 3.5 billion and 4 billion years ago to enable bacterial movement. This study, published in the journal mBio, offers a comprehensive understanding of bacterial stators, proteins that function like pistons in a car engine, according to lead researcher Dr. Caroline Puente-Lelievre from the School of Biological Sciences.

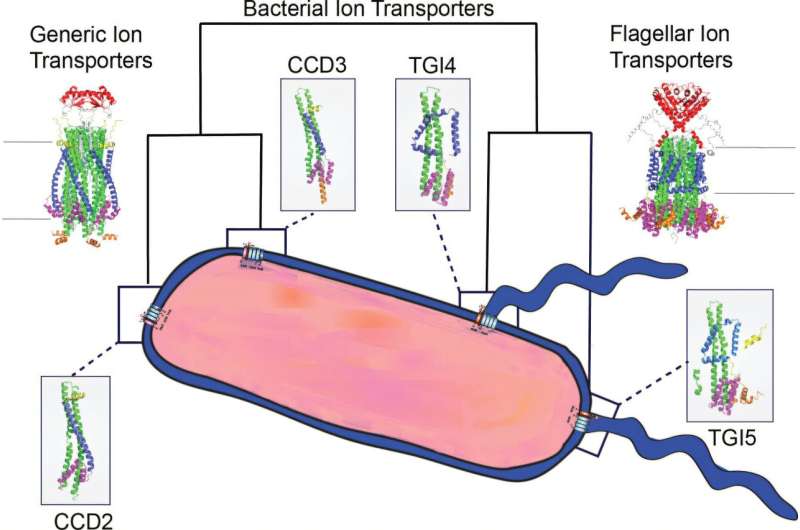

Stator proteins are embedded in the bacterial cell wall, transforming charged particles, or ions, into torque, thereby propelling bacteria through their environments. The research indicates that these stators likely evolved from ion transporter proteins, which are common in bacterial membranes. “Movement is essential to life, from microbes to the largest animals,” Puente-Lelievre stated. “Within our cells, constant molecular motion is what keeps us alive. We’re unraveling the story of how life first got moving.”

Uncovering the Evolution of Bacterial Mobility

The study, conducted in collaboration with UNSW Sydney and the University of Wisconsin Madison, leveraged advancements from DeepMind AI‘s AlphaFold, a revolutionary tool introduced in 2020 that predicts the three-dimensional structures of proteins. During Earth’s early days, characterized by volcanic activity and meteorite impacts, bacteria emerged as single-celled organisms equipped with sophisticated motors. These motors allow bacteria to swim by using stators to drive a rotor, which spins the flagellum, a tail-like structure that propels the cell through liquid.

To study the evolution of stators, researchers analyzed genomic data from over 200 bacterial genomes, created evolutionary trees using computational tools, and conducted laboratory experiments. The three-dimensional shape of each protein was crucial, as its form directly impacts its function.

Puente-Lelievre explained, “We predicted the sequences and structures of ancestral proteins that existed millions or billions of years ago and may no longer exist.” Typically, a stator consists of five identical MotA proteins and two MotB proteins, forming a complex motor system. This dual-protein configuration suggests an evolutionary progression from simpler systems that adapted to various functions, as highlighted by senior researcher Dr. Nick Matzke.

Modern Tools Illuminate Ancient Mechanisms

This research emphasizes the notion that complex biological machines evolve by repurposing simpler components. For instance, just as the ancestors of birds developed protofeathers for warmth and later adapted them for flight, ancient bacteria likely transformed an ion transport mechanism into a motor for mobility.

In their analysis, Puente-Lelievre and her team compared the three-dimensional structures of proteins to identify unique characteristics of stators, including regions responsible for generating torque. “Finally, we performed functional assays in the lab,” she noted. “We took E. coli bacteria that lacked the torque-generating interface and found that none of them could swim, confirming that this specific region is essential for movement in this group of bacteria.”

Despite billions of years of evolution, the fundamental features of these motor proteins remain remarkably unchanged. “We live in a remarkable era for structural biology and microbiology,” stated Assistant Professor Matthew Baker from UNSW Sydney. “New sequences are discovered daily, and tools like AlphaFold allow us to explore potential protein structures almost instantly.”

This research not only sheds light on the origins of bacterial motility but also opens avenues for further exploration into the complexities of life at its most fundamental level.

For more details, see the research article: Caroline Puente-Lelievre et al, “Evolution and structural diversity of the MotAB stator: insights into the origins of bacterial flagellar motility,” published in mBio on March 15, 2025.