Researchers have uncovered a previously unknown genetic lineage in central Argentina that has persisted for at least 8,500 years. This significant discovery sheds light on the region’s population history and the genetic continuity of its Indigenous communities. The findings, published in the journal Nature, highlight the importance of genetic research in understanding human migration patterns in South America.

Insights from Ancient DNA Analysis

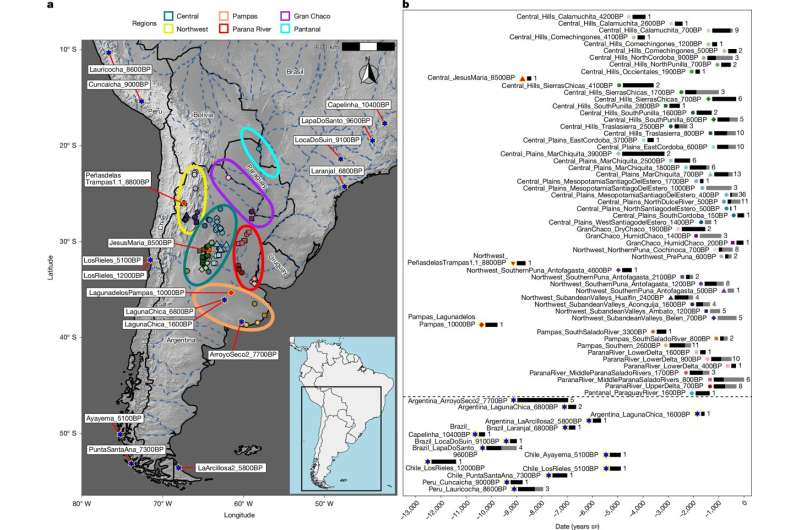

The region known as the central Southern Cone, encompassing much of Argentina, is recognized as one of the last areas globally to be inhabited by humans. Although evidence of migration into the region dates back over 12,000 years, DNA studies in the area have been sparse. To address this gap, a team of researchers conducted a comprehensive genome-wide analysis of ancient individuals from the region.

Analyzing a total of 344 bone and tooth samples from 310 individuals who lived between 10,000 and 150 years ago, the team successfully extracted genome-wide data from 238 of these samples. They focused on over 1.2 million targeted single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) to compare these ancient genomes with previously reported data from 588 pre-European contact Native Americans and contemporary Indigenous populations.

Discovering a Missing Link

The researchers identified a deep genetic lineage that has existed in central Argentina for millennia. This lineage has not only survived various environmental challenges, including prolonged periods of drought, but has also contributed to the genetic makeup of modern Argentinians. The study indicates that this lineage is structured along two main clines: one associated with ancestry from the central Andes and the other connected to the Pampas region.

According to the authors, “We found that the central Argentina lineage is geographically structured along two clines, one reflecting admixture with central-Andes-like ancestry and the other with Middle Holocene Pampas-like ancestry.” This lineage is believed to have coexisted with others, becoming the predominant ancestry in the Pampas region after 800 years ago. Notably, the genetic data suggests that this lineage expanded southward and began mixing with other groups approximately 3,300 years ago.

The genetic connections between communities in central Argentina and the central Andes were established as early as 4,600 years ago. This research provides a clearer genetic framework for understanding the Indigenous population history in Argentina and the broader Southern Cone region.

The persistence of this lineage highlights a remarkable continuity in the region’s genetic landscape, suggesting that while there was some intermingling with other groups, many communities maintained a degree of isolation. The researchers note that evidence for multiple languages existed, yet there was also a striking genetic homogeneity.

Factors contributing to this genetic stability may include kinship-based social structures, which were prevalent in some Argentinian populations. The analysis revealed a pattern of close-kin unions, particularly in northwest Argentina, mirroring similar practices observed in the central Andes. The study authors propose that this might indicate the adoption of the ayllu system—a kinship organization that promotes within-group marriage to enhance cooperation and resource sharing.

Future research efforts, focusing on more densely sampled time series from underrepresented regions and historical periods, could further elucidate the complex interactions and migration patterns of these ancient populations.

This groundbreaking research not only fills critical gaps in the understanding of Argentina’s Indigenous history but also emphasizes the role of ancient DNA in uncovering the narratives of human resilience and adaptation over millennia.