Astronomers have made significant strides in understanding the formation of enigmatic cosmic structures known as “radio relics.” These vast arcs of diffuse radio emissions stretch across millions of light-years and are produced during the slow-motion collisions of galaxy clusters. A newly published study from the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam in Germany reveals crucial insights into how these relics form and behave, addressing long-standing questions in astrophysics.

At the heart of the study are complex shock waves that accelerate electrons to nearly the speed of light. This research, which utilized high-resolution simulations, sheds light on the discrepancies previously noted in the behavior of radio relics. Observations from various telescopes, including NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and Europe’s XMM-Newton, indicated that the magnetic fields associated with these relics are stronger than previously predicted. Furthermore, inconsistencies arose when comparing the strength of shocks measured in radio and X-ray wavelengths, leading to confusion about the mechanics behind their formation.

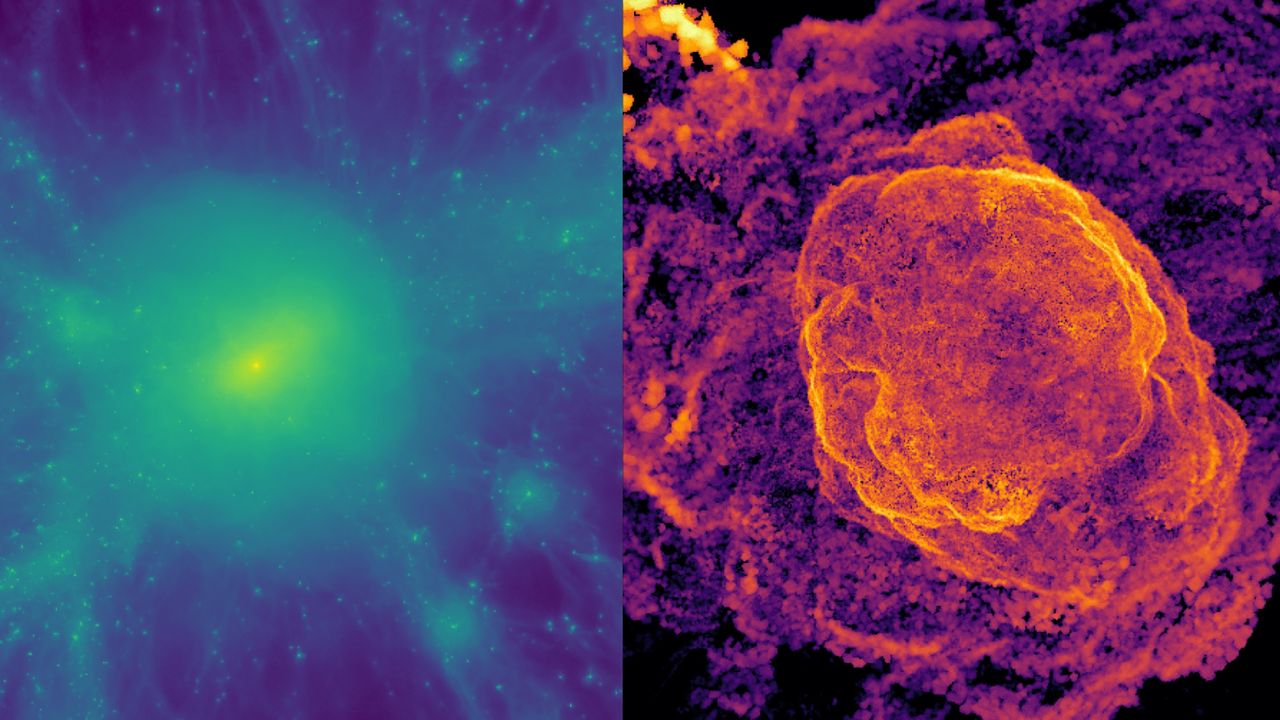

In their research, the team, led by Joseph Whittingham, conducted a comprehensive analysis of the formation and evolution of radio relics. The researchers employed a suite of cosmological simulations to model the growth and collision of galaxy clusters over billions of years. They focused on a particularly energetic merger between two clusters, one approximately 2.5 times heavier than the other. This collision initiated shock waves that spanned nearly seven million light-years.

Building on these findings, the researchers created higher-resolution “shock-tube” simulations to investigate the fine-scale physics occurring at the shock front. By examining how electrons are accelerated as shock waves traverse the turbulent outskirts of galaxy clusters, they were able to derive a clearer understanding of the resulting radio emissions.

The simulations demonstrated that as shock waves extend outward, they collide with other shocks generated by cold gas from the cosmic web. This interaction compresses plasma into dense sheets, leading to a cascade of events that amplify magnetic field strengths, aligning with the unexpectedly strong values observed. As Christoph Pfrommer, a co-author of the study, explained, this mechanism enhances turbulence and compresses the magnetic field, resolving initial questions regarding the relics’ properties.

The research further clarifies that shock fronts interacting with dense gas clumps exhibit localized regions that enhance electron acceleration. While these bright patches dominate radio emissions, X-ray telescopes measure average shock strengths that include weaker areas, elucidating the discrepancies that have puzzled astronomers for years. The findings indicate that only the strongest regions of the shock front contribute significantly to the radio emissions, addressing concerns raised by lower average strengths derived from X-ray data.

The comprehensive approach taken by Whittingham and his team successfully reproduces the combination of magnetic, radio, and X-ray features observed in real radio relics, resolving several long-standing mysteries in the field. The research results will be detailed in a paper accepted for publication in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics and are available on the pre-print repository arXiv as of November 18.

This groundbreaking work not only enhances our understanding of cosmic phenomena but also sets the stage for future studies aimed at unraveling the remaining mysteries surrounding radio relics. The insights gained from this research may provide a deeper comprehension of the processes governing galaxy formation and evolution in the universe.