Recent research has unveiled a new perspective on the formation of Earth-like planets, suggesting that cosmic rays from nearby supernovae may play a significant role. A study led by astrophysicist Ryo Sawada from the Institute for Cosmic Ray Research at the University of Tokyo highlights how interactions between cosmic rays and the early solar system could account for the presence of short-lived radioactive elements crucial for planet formation.

For decades, scientists have theorized that the early solar system was enriched with radioactive materials, specifically aluminum-26, due to a nearby supernova explosion. These elements were believed to heat young planetesimals, leading to the loss of water and volatile substances necessary for forming planets like Earth. However, this classic explanation posed a challenge, as it required an unlikely sequence of events involving the supernova’s proximity and timing.

The traditional model suggested that the supernova must explode at a precise distance—close enough to deliver radioactive material but far enough to avoid destroying the protoplanetary disk. This seemingly rare occurrence raised questions about the likelihood of such conditions facilitating Earth’s formation.

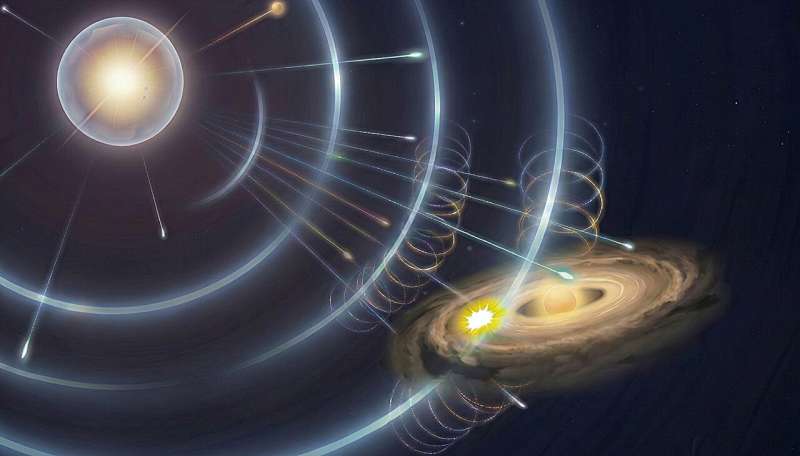

In his exploration of supernova physics and cosmic rays, Sawada questioned whether the early solar system was merely affected by debris from a supernova, or if it was also immersed in a “bath” of cosmic rays. In a study published in Science Advances, his team utilized numerical simulations to investigate the implications of cosmic-ray interactions within the protosolar disk.

The findings revealed an intriguing mechanism: when cosmic rays collide with the protosolar disk, they can trigger nuclear reactions that generate short-lived radioactive elements like aluminum-26. Remarkably, this process operates effectively at a distance of approximately one parsec from a supernova, a typical range within star clusters. This new understanding eliminates the need for an extraordinary coincidence, suggesting that the young solar system simply needed to exist within the same stellar environment as a massive star that would later explode.

This concept of a “cosmic-ray bath” presents a more universal explanation for the formation of Earth-like planets. Many sun-like stars form in clusters, where massive stars are common, and these stars ultimately explode as supernovae. If cosmic-ray baths are prevalent in such stellar nurseries, then the thermal histories that shaped Earth may also be common among other sun-like stars.

The implications of this research extend beyond the formation of Earth-like planets. If planets requiring a supernova encounter are exceptionally rare, then rocky planets with depleted water might be considered unusual. Conversely, if cosmic-ray immersion is a frequent occurrence, then conditions conducive to forming Earth-like planets may exist around a significant number of sun-like stars.

While the study does not claim that supernovae guarantee the emergence of every habitable planet, it highlights the interconnectedness of astrophysical processes. Sawada notes that cosmic-ray acceleration, typically associated with high-energy astrophysics, plays a critical role in planetary science and habitability.

This research serves as a reminder that understanding our origins may not always require additional complexity, but rather a shift in focus to previously overlooked phenomena. The findings encourage a re-evaluation of how cosmic events influence planetary formation and the potential for habitability across the universe.

For further details, refer to the original study: Ryo Sawada et al, “Cosmic-ray bath in a past supernova gives birth to Earth-like planets,” Science Advances, December 21, 2025. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adx7892