Recent research suggests that Earth-like planets may be more common than previously thought, thanks to the influence of distant supernovae. The study, led by Ryo Sawada and published in the journal Science Advances, proposes that a cosmic-ray bath from a supernova occurring within a parsec of our solar system may have enriched the early solar environment with crucial short-lived radioisotopes (SLRs).

Creating an Earth-like planet involves a delicate balance of factors. A planet needs sufficient mass to maintain an atmosphere and generate a magnetic field, yet not so much mass that it retains lighter elements like hydrogen and helium. Additionally, proximity to its star plays a crucial role; planets must be close enough to sustain warmth without losing all their water. Most importantly, they require an abundance of SLRs, which have half-lives of less than five million years, to help warm the early solar system.

According to the research, without these SLRs, Earth-sized planets would likely evolve into Hycean worlds, characterized by vast oceans and thick atmospheres. The presence of SLRs in meteorites, such as the isotope aluminum-26, indicates that our solar system had a rich supply of these elements during its formative years. When aluminum-26 decays, it turns into magnesium-26, providing a clear marker for the presence of radioactive aluminum in ancient cosmic materials.

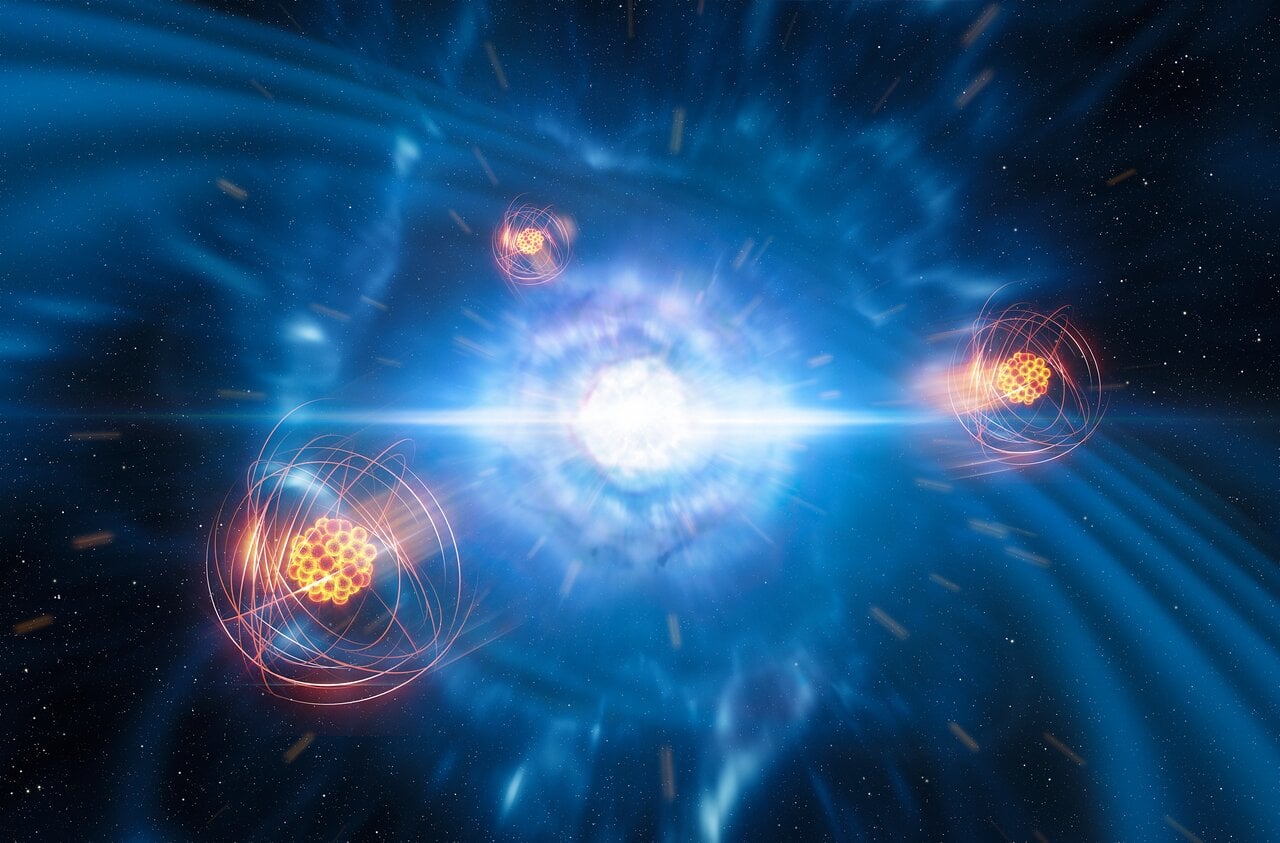

The challenge lies in the fact that SLRs are typically formed in supernovae. A nearby supernova would likely disrupt the protoplanetary disk of a young star, complicating the conditions necessary for planet formation. However, Sawada’s study introduces a compelling alternative. The authors suggest that our solar system was not negatively impacted by a nearby supernova shockwave but was instead enriched by cosmic rays from one located farther away.

This hypothesis implies that if a supernova occurred within a parsec of the early solar system, the resulting cosmic rays could have generated sufficient levels of radioisotopes to match those found in meteorites. Since sun-like stars often form within star clusters, the potential for such supernova events is significant. This enhances the likelihood that terrestrial planets similar to Earth could be relatively common across the galaxy.

The presence of aluminum-26 in the Milky Way serves as a useful indicator of supernova activity. The abundance of this isotope provides insights into the average rate of supernovae, further supporting the plausibility of Sawada’s model. The implications of this research could reshape our understanding of planet formation and the potential for habitable worlds beyond our own.

In summary, the findings from Ryo Sawada and his team not only suggest that the conditions for Earth-like planets may be more favorable than previously assumed but also highlight the intricate connections between cosmic events and the development of planetary systems. As we continue to explore the universe, these insights will drive our quest to understand where life may exist beyond Earth.