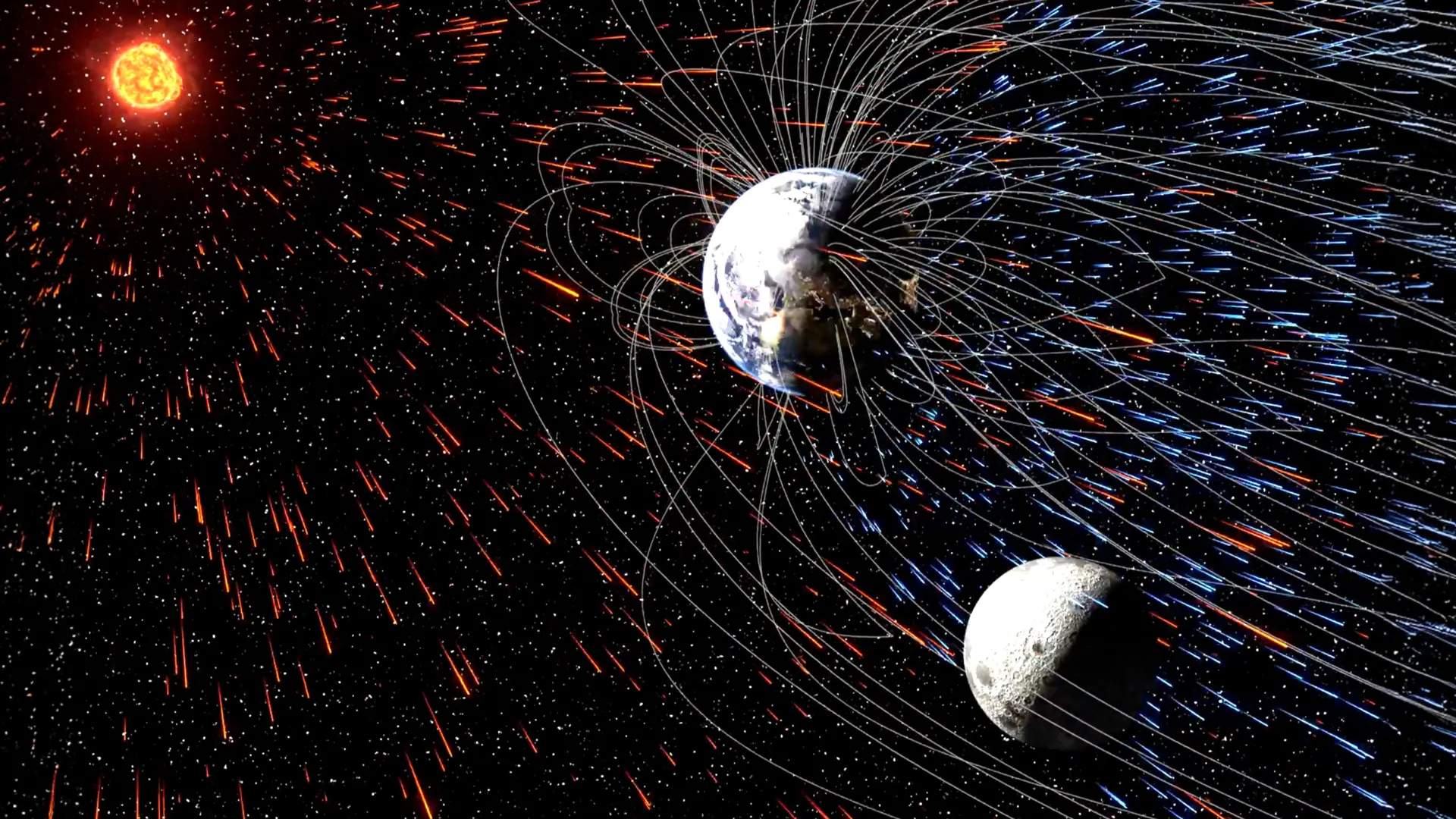

Research from the University of Rochester reveals that Earth’s magnetic field has facilitated the transfer of tiny atmospheric particles to the moon over billions of years. This finding addresses long-standing questions about the origins of certain gases found in lunar samples collected during the Apollo missions and suggests that lunar soil may serve as a historical archive of Earth’s atmosphere.

The moon, often perceived as a barren and lifeless body, harbors a more complex narrative. Scientific investigations indicate that minute fragments of Earth’s atmosphere have been reaching the moon, embedding themselves in its surface. These materials, which may include essential substances for future lunar exploration, have been guided by Earth’s magnetic field rather than blocked by it, as previously assumed.

In a study published in Nature Communications Earth and Environment, researchers demonstrated how atmospheric particles, propelled by the solar wind, can follow invisible lines created by Earth’s magnetic field. This magnetic shield, which has existed for billions of years, enables a slow but steady transfer of material from Earth to the moon.

According to Eric Blackman, a professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Rochester, “By combining data from particles preserved in lunar soil with computational modeling of how solar wind interacts with Earth’s atmosphere, we can trace the history of Earth’s atmosphere and its magnetic field.” This research not only sheds light on the moon’s potential as a resource for future astronauts but also suggests that it may hold a valuable record of Earth’s environmental history.

Uncovering the Mysteries of Apollo Samples

The Apollo missions of the 1970s provided crucial samples for this research. Analysis of lunar rocks and soil, known as regolith, revealed the presence of volatile substances such as water, carbon dioxide, helium, argon, and nitrogen. While some of these materials are understood to originate from the solar wind, the quantities—particularly of nitrogen—exceed what solar wind alone could account for.

In 2005, scientists from the University of Tokyo proposed that these volatiles might have been derived from Earth’s atmosphere before the planet developed its protective magnetic field. They believed that once the magnetic field was established, it would hinder atmospheric particles from escaping into space. The findings from the Rochester team contradict this view.

Simulating Atmospheric Transfer

To unravel the mechanics of how these atmospheric particles journey to the moon, the research team employed advanced computer simulations. The team, which included graduate student Shubhonkar Paramanick, Professor John Tarduno, and computational scientist Jonathan Carroll-Nellenback, tested two scenarios: one modeled early Earth without a magnetic field and a stronger solar wind, and the other represented present-day Earth, equipped with a robust magnetic field and a weaker solar wind.

Results indicated that the modern Earth scenario allows for significantly more effective particle transfer to the moon. Charged particles from Earth’s upper atmosphere can be dislodged by the solar wind and follow magnetic field lines that extend into space, intersecting the moon’s orbit. Over the course of billions of years, this process continuously deposits small amounts of Earth’s atmosphere onto the lunar surface.

The implications of these findings are profound. The moon is not merely a silent witness to Earth’s history but may also contain a chemical record of the planet’s atmospheric evolution. By examining lunar soil, scientists could gain insights into how Earth’s climate, oceans, and life itself have transformed over millennia.

Furthermore, the steady influx of atmospheric materials suggests that the moon could harbor more valuable resources than previously thought. Elements such as water and nitrogen could prove vital for sustaining long-term human presence on the moon, potentially reducing the need for supply shipments from Earth.

As Paramanick notes, “Our study may also have broader implications for understanding early atmospheric escape on planets like Mars, which lacks a global magnetic field today but had one similar to Earth in the past.” This research offers a new perspective on how planetary evolution and atmospheric dynamics can influence habitability.

The study received support from NASA and the National Science Foundation, highlighting the collaborative effort to expand our understanding of both Earth and its celestial neighbor. As researchers continue to explore these connections, the moon may emerge as an even more critical element in the ongoing story of human exploration and our place in the cosmos.