A recent study utilizing data from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory has revealed that many smaller galaxies may not contain supermassive black holes at their centers. This finding challenges the prevailing notion that almost all galaxies host these massive cosmic entities. The research, which examined over 1,600 galaxies over two decades, shows that smaller galaxies, such as PGC 039620, are significantly less likely to harbor supermassive black holes compared to their larger counterparts.

The study analyzed a diverse sample of galaxies, ranging in mass from over ten times that of the Milky Way to dwarf galaxies with a stellar mass of only a few percent of our galaxy. The results were published in The Astrophysical Journal in March 2023, shedding light on the formation and distribution of black holes in different galaxy types.

Fan Zou, a researcher from the University of Michigan and the study’s lead author, emphasized the importance of accurately counting black holes in smaller galaxies. “It’s more than just bookkeeping. Our study gives clues about how supermassive black holes are born,” Zou stated. The research also provides insights into how future telescopes may detect black hole signatures in dwarf galaxies.

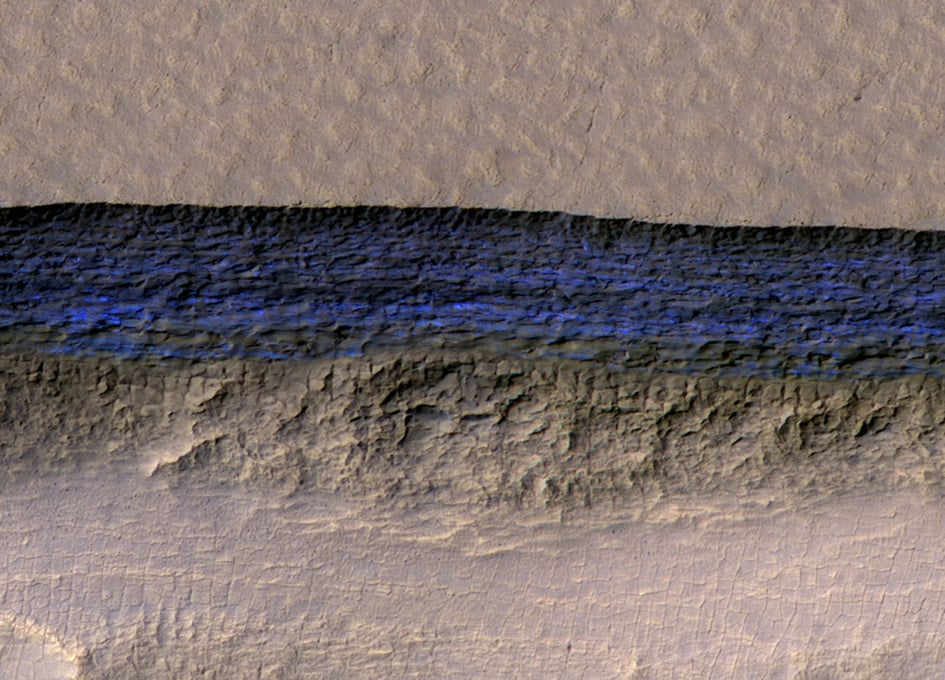

The Chandra Observatory captured X-ray emissions from galaxies, which are indicative of supermassive black holes. The analysis indicated that more than 90% of massive galaxies, including those comparable to the Milky Way, exhibit bright X-ray sources, a clear sign of supermassive black holes. In stark contrast, smaller galaxies typically show a lack of these unmistakable signals.

The researchers discovered that galaxies with masses below three billion solar masses, similar to the Large Magellanic Cloud, generally do not emit bright X-ray sources. To explain this phenomenon, the team considered two possibilities: either the rate of black holes in less massive galaxies is significantly lower, or the X-rays produced by black holes in these galaxies are too faint for detection by Chandra.

Elena Gallo, another author from the University of Michigan, supported the first hypothesis, stating, “We think, based on our analysis of the Chandra data, that there really are fewer black holes in these smaller galaxies than in their larger counterparts.” The researchers found that the amount of gas falling onto black holes affects their brightness in X-ray emissions. Smaller black holes, expected to attract less gas, would naturally be fainter and harder to detect.

Interestingly, the study also revealed an additional deficit of X-ray sources in small galaxies beyond what would be expected from the decline in gas availability. This suggests that many low-mass galaxies might not have any black holes at all. The conclusion points to a genuine decrease in the number of black holes in these smaller galaxies, which could significantly impact our understanding of black hole formation.

There are two primary theories regarding the origin of supermassive black holes. One suggests that massive gas clouds collapse directly into a black hole, while the other posits that these black holes form from smaller black holes created when massive stars collapse. Anil Seth, co-author of the study from the University of Utah, noted that if the latter theory were valid, smaller galaxies would likely possess black holes at similar rates as larger galaxies.

The findings support the idea that giant black holes are often born with substantial initial masses, potentially thousands of times that of the Sun. This challenges the notion that smaller black holes, which might result from stellar collapses, could account for black holes in smaller galaxies.

These insights have broader implications, including the expected rates of black hole mergers as dwarf galaxies collide. A reduced number of black holes could lead to fewer detectable sources of gravitational waves in the future, as well as a diminished capacity for black holes to disrupt stars within dwarf galaxies.

NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, oversees the Chandra program, while the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory’s Chandra X-ray Center manages its scientific operations from Cambridge, Massachusetts, and flight operations from Burlington, Massachusetts.

As our understanding of the universe evolves, this research opens new avenues for exploring the nature of black holes and their role in galaxy formation.