An international research team led by scientists from the University of Toronto and the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine has developed a groundbreaking resource to identify individuals at genetic risk for elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL), commonly referred to as ‘bad’ cholesterol. This cholesterol type is known to significantly contribute to heart disease. The team has classified nearly 17,000 missense coding variants of the LDLR gene, providing crucial insights into the relationship between genetic variations and LDL receptor function.

The research, published in the journal Science, offers a detailed mapping of how these variants affect the structure and uptake of LDL receptor proteins. Such a comprehensive resource is expected to assist clinicians in predicting patients’ risk for heart attacks and strokes, enabling timely preventive measures. The authors draw parallels between their findings and the early detection capabilities brought about by identifying mutations in the BRCA1 breast cancer gene, which has been instrumental in saving lives through early intervention.

“Even with normal LDL levels, a person might be at an elevated risk of a heart attack due to disease-causing variants in the LDL receptor,” stated Frederick Roth, PhD, professor and chair of computational and systems biology at Pittsburgh. “By identifying damaging LDL receptor variants, clinicians can initiate preventive treatment early on and mitigate risks.”

Understanding LDL Cholesterol Risks

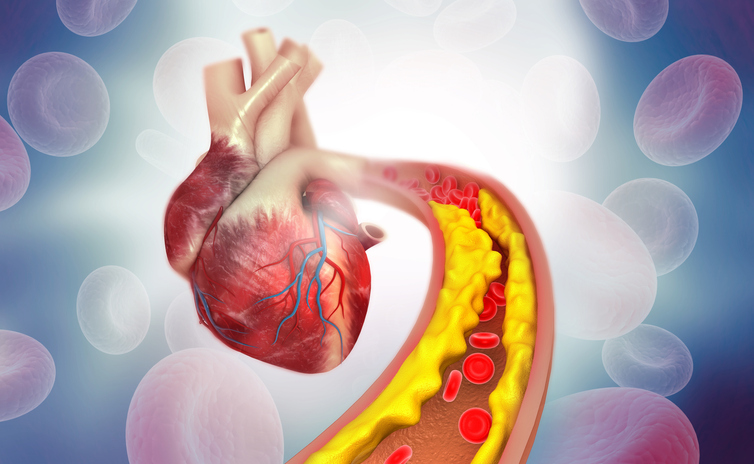

Heart disease remains the leading cause of death in the United States, accounting for nearly 700,000 fatalities annually. While lifestyle factors such as diet and exercise play a role, genetic predisposition significantly influences the accumulation of plaque in coronary arteries. Variants in the LDLR gene are a primary factor in these risks, particularly in cases of familial hypercholesterolemia (HeFH), a condition characterized by elevated LDL cholesterol levels.

The authors note that genetic variants in the LDLR gene can disrupt the clearance of LDL, which is critical in maintaining heart health. They emphasize, “Heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia—defined by an increase in circulating LDL cholesterol—is among the most common and severe genetic causes of cardiovascular disease.” The study indicates that genetic variants in LDLR account for roughly 80% of molecularly diagnosed HeFH cases.

LDL’s role in healthy blood vessels is to transport ‘good’ cholesterol, essential for cell membranes and the production of hormones and vitamins. However, mutations that reduce LDL receptor efficiency can result in dangerously high LDL levels. The identification of pathogenic LDLR variants is crucial for accurate diagnosis and effective management of cardiovascular risks.

Challenges in Genetic Interpretation

Modern gene sequencing technologies can read a person’s complete genetic code from a small tissue sample within hours. Despite this capability, interpreting the vast data remains complex, particularly as the functional consequences of most variations in the LDLR gene have historically been unclear. The researchers highlight that definitive clinical classifications are lacking for nearly half of the LDLR missense variants encountered, which hampers timely diagnosis and patient risk stratification for HeFH.

To address this gap, Roth and his team have classified nearly 17,000 LDLR gene modifications alongside their effects on LDL receptor protein structure and function. They measured both LDL uptake and receptor abundance to create a table that reflects each variant’s mechanism of action and impact on LDL clearance efficiency.

The resulting sequence-function maps offer significant insights into LDLR function and have the potential to inform clinical variant interpretation and enhance patient risk estimation for HeFH. “Functional scores correlated with hyperlipidemia phenotypes in prospective human cohorts and augmented polygenic scores to improve risk inference,” the authors noted.

Implications for Clinical Practice

Study co-author Dan Roden, MD, a clinician-scientist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, remarked, “New unclassified variants are seen all the time in the clinic, and we often don’t have the evidence we need to inform patient care. These variant impact scores have the potential to increase the number of diagnoses of familial high cholesterol for those with unclassified variants by a factor of ten.”

Additionally, the study uncovered a subset of LDL receptor variants whose ability to uptake LDL was inhibited by high levels of very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), a larger precursor to LDL. “The influence of VLDL on LDL uptake was an unexpected finding. We’re excited about investigating this further and understanding potential implications for human health,” said Daniel Tabet, PhD, the first author of the study.

This cholesterol-focused initiative is part of a broader research effort co-founded by Roth, known as the Atlas of Variant Effects Alliance. The alliance involves over 500 scientists from 50 countries working to create comprehensive maps that evaluate gene variants associated with various diseases.

As this research continues to develop, it holds promise for transforming the landscape of cardiovascular health diagnostics and enhancing the ability to address genetic risks in patients, potentially saving lives through earlier and more effective interventions.