An international research team has made a significant discovery by documenting the first fossilized vertebrate footprints from the Quaternary period in the fossil dune deposits of Murcia, Spain. This groundbreaking finding is attributed to the elephant species Palaeoloxodon antiquus, commonly known as the straight-tusked elephant. The study, titled “New vertebrate footprint sites in the latest interglacial dune deposits on the coast of Murcia (southeast Spain). Ecological corridors for elephants in Iberia?” was published in the journal Quaternary Science Reviews.

The research sheds light on the movement patterns of megafauna during the Last Interglacial, approximately 125,000 years ago. The fossilized footprints, discovered in coastal landscapes, provide valuable insights into the paleoecology of the Iberian Peninsula. The study was coordinated by Carlos Neto de Carvalho, from the Geology Office of the Municipality of Idanha-a-Nova and the University of Lisbon, along with contributions from researchers at the University of Seville, the Andalusian Institute of Earth Sciences in Granada, and the University of Huelva.

Fossil Footprints Reveal Diverse Ecosystem

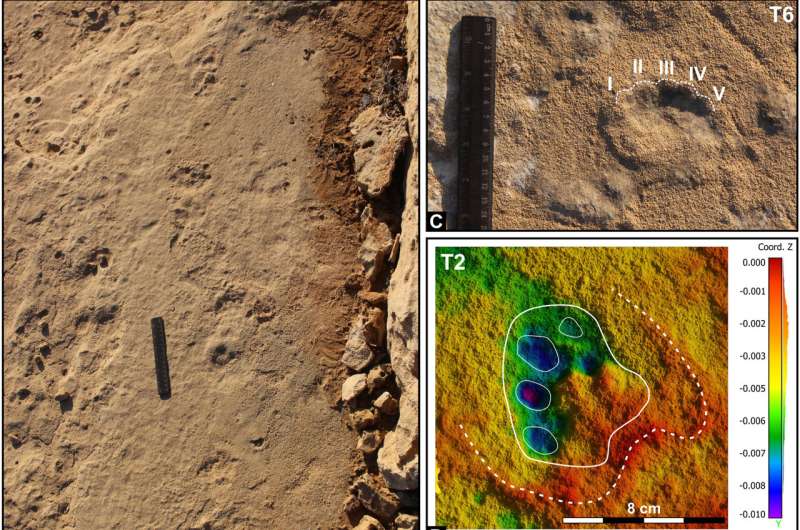

The research team identified four key areas with fossil footprints, indicating a diverse community of mammals inhabiting a coastal forest ecosystem during the marine isotopic stage (MIS 5e). The most notable discovery was made at Torre de Cope, where a 2.75-meter-long trackway of a proboscidean was preserved, featuring four rounded footprints measuring between 40–50 cm in diameter. This arrangement, characteristic of the quadrupedal gait of elephants, suggests the trackway belonged to an adult Palaeoloxodon antiquus, approximately 2.3 meters tall at the hip, over 30 years old, and weighing around 2.6 tonnes.

In addition to the elephant tracks, the researchers found evidence of other species. Traces of a medium-sized mustelid were discovered in Calblanque, consisting of a 1.5-meter-long trail with ten circular footprints that indicate slow movements near water sources. An isolated footprint of a canid, measuring 10 × 8 cm with claw marks, points to the presence of predators such as wolves (Canis lupus) in the area. Furthermore, bifid footprints compatible with red deer (Cervus elaphus) were found, illustrating movement through dunes and scrubland. A young equid (Equus ferus) trail, marked by footprints measuring approximately 10 × 12 cm, represents the most recent record of this species in the southeastern region of the Iberian Peninsula.

Implications for Pleistocene Ecology

The findings regarding coastal corridors for megafauna provide broader insights into the Iberian Peninsula’s ecological significance during the Pleistocene. This region likely served as a climate refuge for various species and as a migratory route for large mammals, including elephants. The study connects these ecological corridors to paleoanthropology, noting a geographical overlap between the elephant migration routes in southeastern Iberia and sites where Neanderthals are known to have lived.

The coastal areas of Murcia may have been rich in resources, forming critical zones for hunting and sustenance for Neanderthal populations. This research not only enriches our understanding of prehistoric biodiversity but also highlights the importance of these coastal landscapes in the evolutionary history of both fauna and early human inhabitants.

For further details, the study can be referenced through the Quaternary Science Reviews journal, under the DOI: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2025.109631.