Researchers at Space Park Leicester have unveiled a groundbreaking project aimed at exploring the effects of space on living organisms. The newly developed Fluorescent Deep Space Petri-Pod (FDSPP) will enable remotely operated biological experiments in microgravity and is funded by the UK Space Agency with support from Voyager Technologies.

As humanity sets its sights on a sustained presence beyond Earth—be it in orbit, on the Moon, or further—understanding the biological challenges of prolonged space missions becomes increasingly vital. The FDSPP is designed to investigate how microgravity and radiation impact the development of organisms, particularly focusing on the early stages of life. The findings could have significant implications for the health and well-being of astronauts on extended missions.

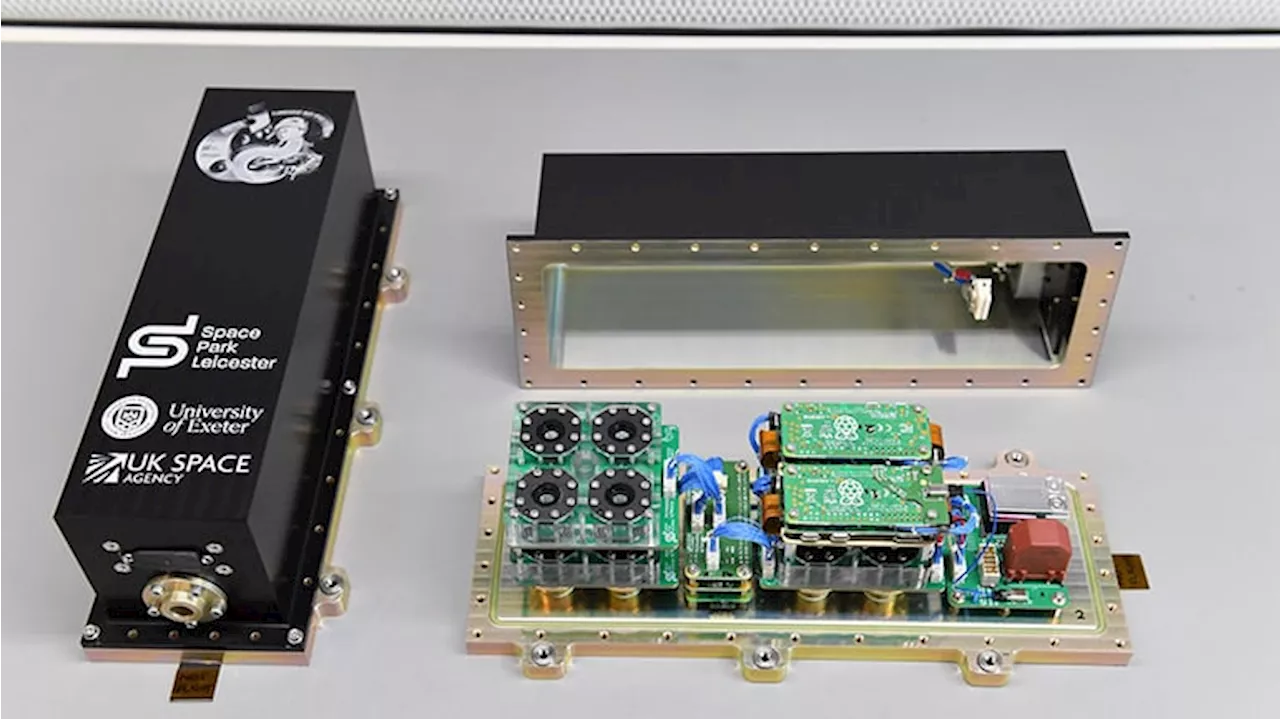

The team at the University of Leicester has engineered the FDSPP to be a compact, self-contained unit measuring approximately 10x10x30 cm and weighing around 3 kg. It features 12 Petri-Pods designed to maintain a stable atmosphere and temperature for organisms, ensuring they receive essential nutrients while exposed to the harsh conditions of space.

Inside the FDSPP, researchers will deploy C. elegans nematode worms, which will be monitored using fluorescent markers installed prior to launch. These markers will facilitate real-time health assessments through imaging and time-lapse video while the experiment is conducted aboard the International Space Station (ISS).

Understanding the Risks of Space Travel

Prolonged exposure to microgravity has already been linked to various health issues, including bone density loss, muscle atrophy, and changes in vision. Furthermore, radiation exposure poses serious risks such as genetic damage and an increased likelihood of cancer. The FDSPP aims to tackle unanswered questions regarding the long-term effects of living in space, particularly how organisms age and develop under these conditions.

The experiment is scheduled for launch in April 2026 as part of a cargo flight to the ISS. Following a brief period inside the station, the FDSPP will be deployed outside for a duration of 15 weeks. During this time, it will be subjected to the vacuum of space and monitored for temperature, pressure, and radiation exposure. Data collected will be transmitted back to Earth for analysis.

Professor Mark Sims, the project manager for the FDSPP at Leicester, emphasized the significance of this experiment, stating, “This mission will demonstrate the flight readiness of FDSPP, and we believe its success will help position the UK amongst the global leaders in life sciences research for future low Earth orbit, Lunar, and Mars missions.”

Collaborative Efforts for Future Research

The project also highlights the importance of collaboration between biologists and engineers. Professor Tim Etheridge, the principal investigator from the University of Exeter, noted that such research is essential for developing medical treatments and mitigation strategies to address the health impacts of spaceflight.

As humans prepare for long-duration missions, understanding whether children and animals can be safely raised in space remains a critical question. The findings from the FDSPP could pave the way for future explorations and the establishment of permanent human habitats beyond Earth.

The FDSPP represents a significant step forward in space biology research and aims to contribute valuable insights into the challenges of living and working in the unique environment of space.