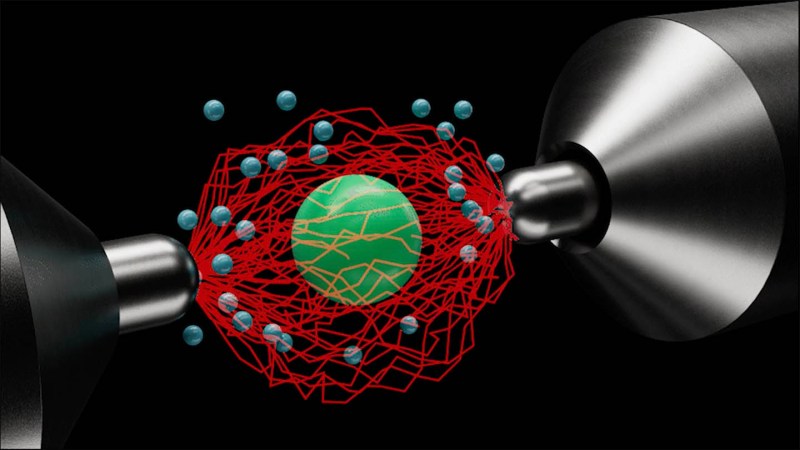

A groundbreaking study published in Physical Review Letters reveals that a tiny glass sphere, measuring just 5 micrometers in diameter, acts like an incredibly efficient engine, achieving an effective temperature equivalent to 13 million Celsius. This remarkable feat was accomplished by levitating the sphere in a near-vacuum using an electric field, causing it to oscillate violently.

The phenomenon observed does not involve traditional heat but rather the energy of the glass sphere’s motion. According to physicist James Millen from King’s College London, “It is moving as if you had put this object into a gas that was that hot. It moves around like crazy.” This effective temperature is significant, as it opens avenues for exploring the physics of extreme temperatures at the microscale, an area that remains poorly understood.

Unusual Behavior and Potential Applications

The sphere’s performance is intriguing not just because of its extreme temperature but also due to its fluctuating efficiency. Researchers found that the engine’s efficiency varied widely, sometimes reaching 200 percent and other times dropping to 10 percent. In some instances, the engine even operated in reverse, cooling down instead of heating up. This unpredictability reflects the bizarre nature of thermodynamics on such a small scale.

John Bechhoefer, a physicist at Simon Fraser University, noted the impressive achievement, stating, “Creating effective temperatures that high at that scale is very nice.” The study demonstrates that the effective temperature depends on the object’s size, suggesting that larger engines could potentially reach even higher temperatures.

The implications of this research extend into biological science. The unique properties of this glass sphere could provide insights into microscopic biological engines, such as kinesin, a motor protein that transports cargo within cells. Millen explained that understanding such microscale thermodynamics is crucial for grasping how tiny structures in biological systems function, particularly in the context of protein folding.

Significance of the Findings

Creating an engine that combines extreme temperatures, a high hot-to-cold temperature ratio, and position-dependent diffusion is a rare achievement in physics. Uroš Delić from TU Wien expressed enthusiasm about the research, stating, “This work combines all three, so that’s quite cool — or hot.”

The findings reveal that thermodynamics at the microscale can be as unintuitive as quantum mechanics, as characterized by Millen. This new understanding could pave the way for future experiments and innovations in both scientific research and engineering design.

While the glass sphere may not serve practical applications in its current form, it acts as a crucial analog for scientists seeking to study the complex behaviors of microscopic engines. By manipulating this tiny glass sphere, researchers hope to unlock further mysteries of thermodynamic principles that govern life at the cellular level.