BREAKING: Researchers at New York University have made a groundbreaking discovery, uncovering thousands of preserved metabolic molecules inside fossilized bones dating back 1.3 to 3 million years. This urgent research provides unprecedented insights into ancient animal diets, diseases, and the climate of their environments.

This remarkable study, published in the journal Nature, reveals that these bones contain chemical traces that allow scientists to reconstruct details about ancient ecosystems. The findings suggest that these prehistoric environments were significantly warm and wet, contrasting sharply with today’s conditions.

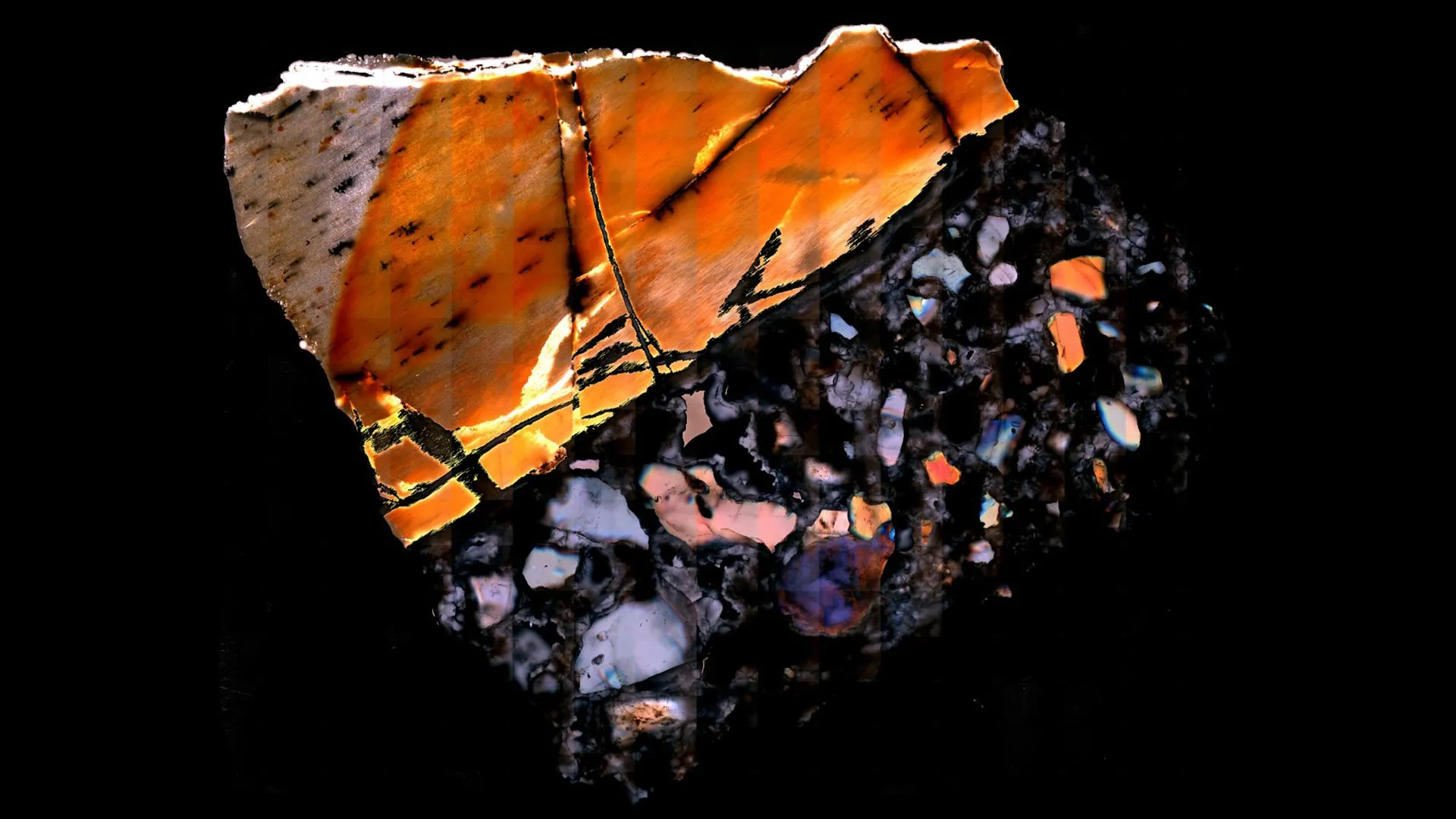

The researchers utilized advanced techniques to analyze the metabolic signals preserved in the bones, offering a unique window into the health and nutrition of these long-extinct species. Notably, one fossilized ground squirrel bone from Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania showed evidence of a parasite known today, Trypanosoma brucei, which causes sleeping sickness in humans.

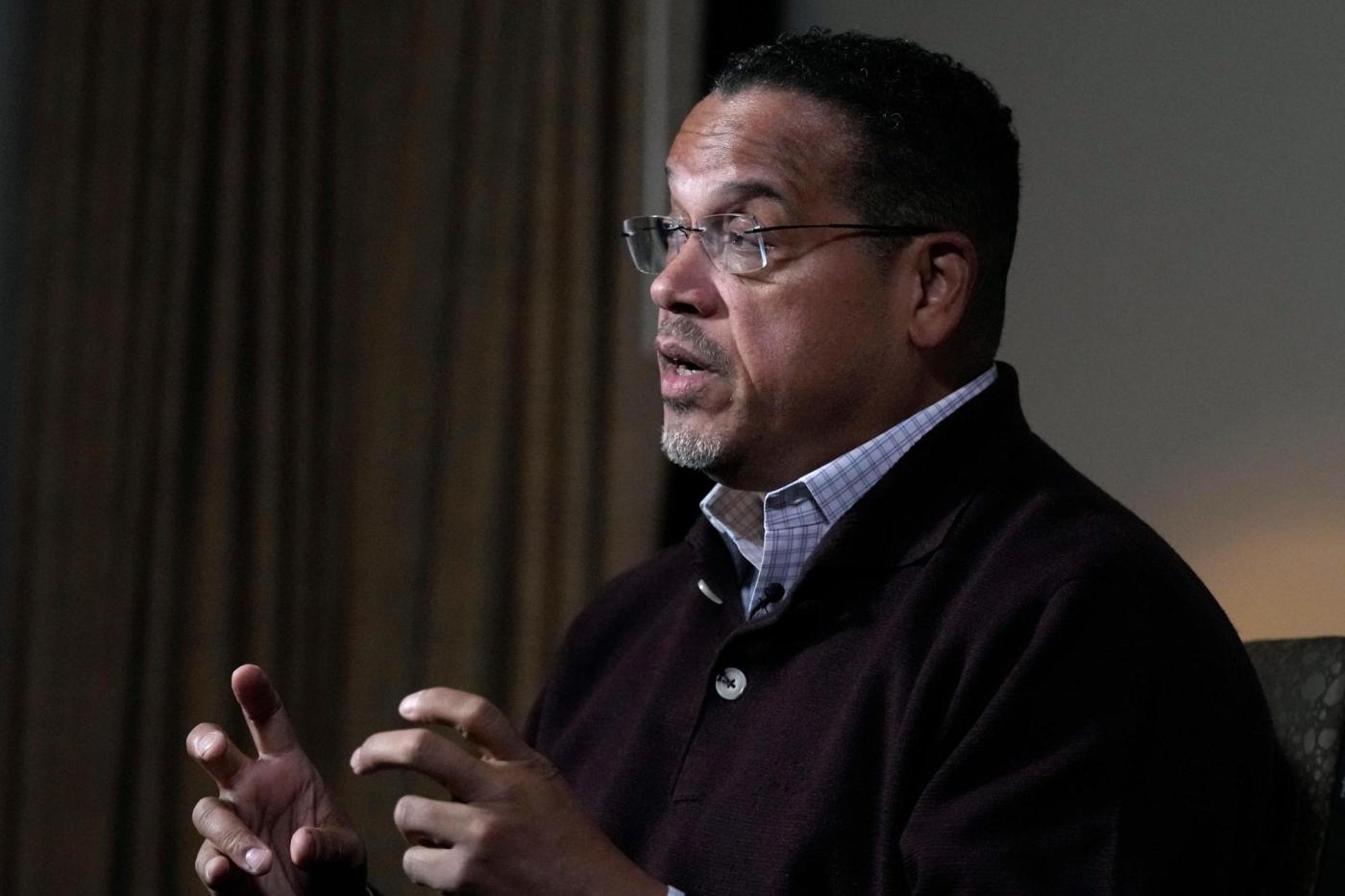

“This is a game changer for understanding early life,” said lead researcher Timothy Bromage, a professor of molecular pathobiology at NYU. “We can now trace the effects of ancient climates on animal health and diets with a level of detail previously unimaginable.”

The fossil samples, excavated from regions rich in early human activity, include bones from rodents and larger mammals such as antelopes and elephants. The team identified thousands of metabolites, revealing how these animals interacted with their environment and what they consumed. For instance, certain metabolites pointed to a diet that included local plants like aloe and asparagus, enabling scientists to infer specific climatic conditions of the time.

Researchers have long relied on DNA analyses for insights into ancient life, but this innovative approach—dubbed metabolomics—has rarely been applied to fossils. By confirming that metabolites can survive in fossilized bones, the team is poised to revolutionize how scientists study ancient ecosystems.

The implications of this research extend beyond academic interest. Understanding the biological and environmental factors that shaped prehistoric life can inform current climate change discussions and biodiversity conservation efforts.

As this research gains traction, further studies are underway to explore the full potential of metabolomics in paleontology. The team, which includes international collaborators from France, Germany, and Canada, is eager to continue unraveling the secrets of ancient life.

Stay tuned for more updates on this developing story, as researchers continue to shed light on the complex interactions between early life forms and their environments. This groundbreaking work not only enhances our understanding of the past but may also guide future ecological strategies.